Confused Seas

🌊 🌊

I knew we were in trouble when we crested a wave and smashed into a tree.

Trees aren’t, generally speaking, supposed to be out in the ocean. Of course, trouble had been mounting long before we actually hit something, but the way it formally announced itself is etched in my mind: a twenty foot long tree, taken out to sea by the windstorm, riding the seas and hidden in the trough between two large waves. Dangerous situations often build just like this, degree by degree, fooling the rational mind until some event pushes things over the edge and the lizard or monkey or whatever brain kicks in and says, “fuck this!”

That moment landed for me the exact same moment our little boat landed smack dab on the middle of that tree trunk. The noise of the exploding timbers, the shudder of the aluminum boat happened and the sight of thousands of timber shards disappearing over the next wave just as quickly as they’d come made my primal brain take over.

“Go now!” It screamed inside my mind, as I white knuckled the wheel.

That split second, however, is often when trouble turns into disaster.

I remember my Dad once asked me, “What do you do if you’re flying alone at night and can’t find a landmark, and you notice you’re past the halfway point on fuel, and ohhh maybe you’re taking on a bit of ice too?”

I stared at him blankly. I hadn’t the foggiest idea. We were cruising along in the plane on a grocery run to Western Alaska and it was a calm, sunny, winter day. I’d read Hatchet by that point (pretty much a requirement for outdoor Alaskan kids) and while I believed I could handle a plane better than that kid had, my Dad’s scenario was far beyond that book and my own meager abilities. I kept looking at him in silence, figuring he’d tell me.

“Well, I’ll tell you what you don’t do,” he continued after a long pause, “Panic. If you panic you die.”

With that he took a bite of a sandwich thoughtfully, steering us through the air with his knees while he ate, and concluded, “But if you don’t panic, well, then you just might figure something out.”

Such is bush pilot wisdom. Effective, but indirect; helpful, but not comforting. The unspoken moral, of course, being: don’t get into such a situation in the first place. Yet, I think he also knew that sometimes they happen despite our best efforts. Remembering this advice convinced me I still had my head and though it might have been too late for prevention, we still had a chance at a cure.

We had a few things going for us: Foremost, we’d been lucky — we still had our boat. The V-shaped hull had split the tree and driven each half outward as we passed, preventing our engine from being ripped clean off. It ran strong and I took that strength and made it my own. Second, time was on our side. We had a full tank of fuel and the long Alaska summer days meant that, despite the rain that had blown in, we wouldn’t have to feel our way through nasty seas in the dark. Last, but not least, we knew exactly where we were.1

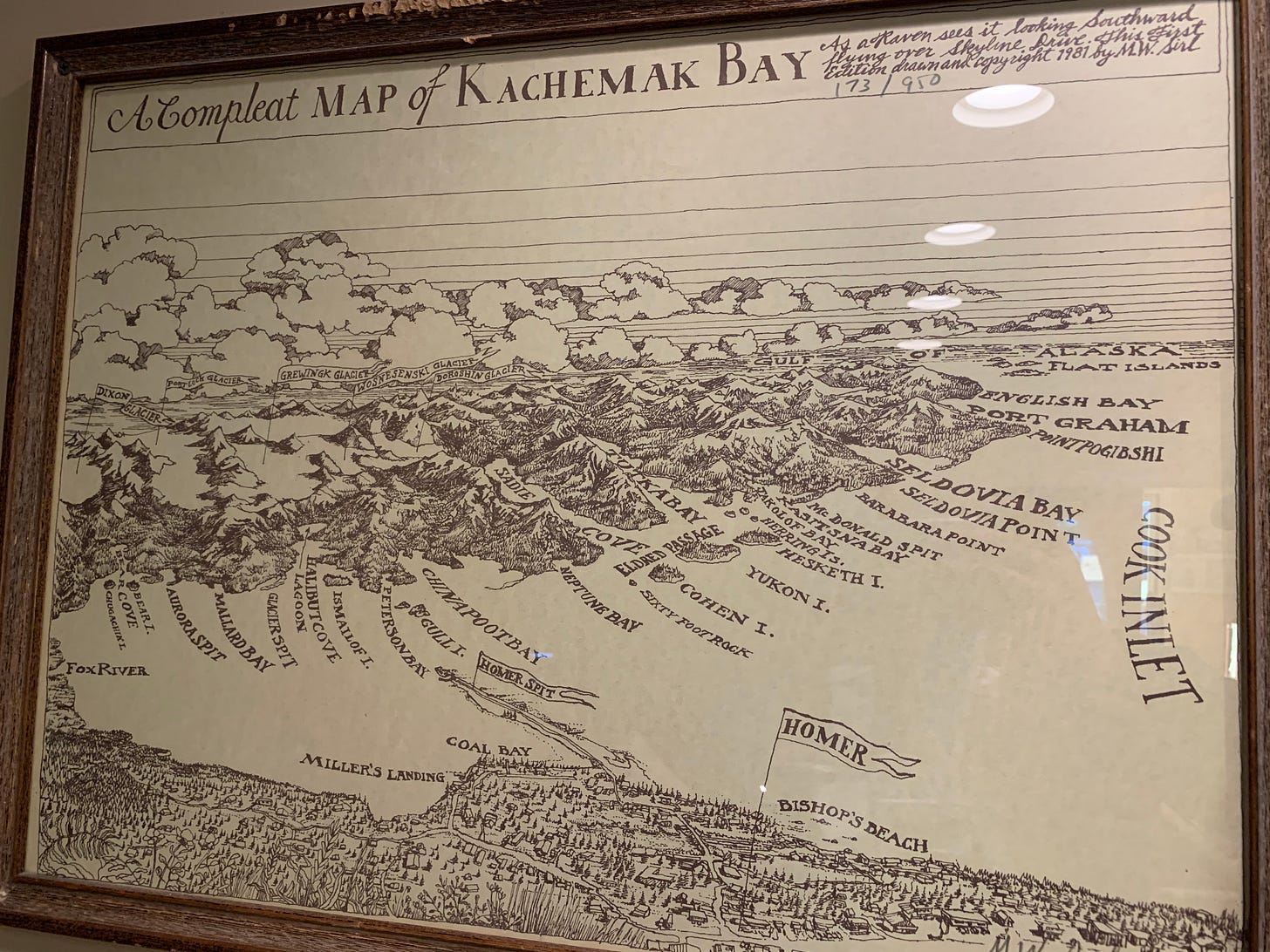

Our group of four had been trying to run up the coast of Kachemak Bay in our small aluminum boat from the small town of Seldovia north to Halibut Cove where we were promised art, fresh oysters, and cocktails. The weather report forecast some wind, but nothing major, and the prospect of light rain. When we’d left the harbor that morning it had started blowing a bit, but nothing out of the ordinary and the sun shone. The trip was easy. We stopped to hike for a couple hours and, as we got back in the boat I noticed the wind had picked up. Since we had friends on board, I tucked us behind Yukon Island to get a calmer ride as we turned out toward our next destination. Ever cautious, I told everyone that we’d just stick our heads out into the bigger water and take a peek; we could always turn around and skedaddle back south from whence we came. As we left the lee of the islands, I noticed the wind picked up enough to push between the seams of the boat’s bright blue canvas top and drove the waves a bit higher.

The first problem is that as we picked our way north, those waves kept building. The second problem, which is a bit sneakier, is that they took their sweet time in doing so which was time that we spent getting further from the safety of the islands and our protected run back to town, each passing moment making our exposure all the longer if ever we did decide to turn around. The third problem, the insidious wildcard that I hadn’t properly planned for, the thing that almost turned an uncomfortable day into a disaster, was the tide change.

The third problem, the insidious wildcard that I hadn’t properly planned for, the thing that almost turned an uncomfortable day into a disaster, was the tide change.

Once, many years before and just a couple miles down the coast from where we’d just landed on the tree, I crawled out of my tent in the middle of the night to pee and found that same little aluminum boat lying akimbo on a slanted field of boulders, like it’d been dropped from the sky. Of course, it had been dropped by the ocean instead, which set it down onto that steep hill strewn with rocks the size of cars before retreating a football field away. Yet I didn’t worry, because I had a little pocket-sized tide book stuffed in my coat that promised the water would return in the morning. I had stayed up the night before with my brother drinking scotch, pushing out the boat bit-by-bit with the ebbing tide, and paying out line until we were satisfied we’d gone far enough that the next day’s high tide would lift the boat again. We measured beach-lengths with a rifle, did some rough trig under the influence of Lagavulin to determine the vertical drop, and toasted to a job well done.

The point is that I knew how tides worked in that area. I knew how far they dropped in just six hours. From there, it isn’t much of a leap to understand that achieving that time table requires roughly a shit load of water to move out of those bays very quickly. Yet I had never experienced the combination of high winds pushing the sea in one direction while a powerful outgoing tide pulls it in another. Worse in our case, the winds and the tide were perpendicular to each other. This creates what is called a “confused sea” where waves come from multiple directions, swirling, crashing into one another, sometimes stacking into something bigger.

Checking the map I could see we were just off China Poot Bay. That triggered a dim memory of a brightly lit warning sign, like those used in road construction, stationed at the top of the boat ramp a few days before. Its flashing letters had warned that during tidal changes small craft had a danger of capsizing at China Poot Bay. I knew that if the boat flipped, and we all went in the water, it was game over. Even on a calm day, the water temperature would overcome us in minutes. But during a windstorm there was little chance of staying together — let alone making it to shore and staying warm.

Off our port side I saw the lights of the Homer Spit squiggling faintly on the horizon through the falling rain and clear, crinkled plastic of our boat’s canopy windows. Hotels, restaurants, and my truck with the boat trailer were all there somewhere amid the dim but alluring twinkles and I felt their gravitational pull, only five miles away. It wasn’t the plan — all of our gear was back in the cabin in Seldovia — but beat going in the drink, washing up on a beach, or trying to fight the seas back south. I made the call and, we as crested the next giant wave and started down the backside, turned us sideways to follow along inside its trough.

Distance is absolute, but the time doubly relative. The rough seas both limited our actual speed and heightened our senses to such a degree that every moment passed like an hour. We spent that eternity in silence, picking our way toward the lights shining like salvation on the Spit. Worse, we couldn’t drive straight at our target because of the waves coming at us from the side. We had to quarter into the swell zigging off course south and then zagging back north at 45 degrees. Whenever a particularly big wave rolled through I’d turn our nose completely off course to meet it head on, our pointed bow cutting through it and throwing spray clean over the roof of the canopy. I held the wheel in one hand and the throttle in the other, constantly adjusting our speed to push up the front of the swell before cutting it to glide down the back. WHRRRRRR-urrrrrrrr-WHRRRRRR-urrrrrrrr, up and down, up and down.

The GPS showed us moving at 3.7 miles per hour which, coupled with our swerving track, meant we must have been out there for close to two hours. On a clear day it would have been 20 minutes. Yet I didn’t rush. I held it in hand, spun the wheel, listened to the crash of the sea as it broke over the bow, the squeaking swish of our little windshield wiper as it beat back and forth, and the comforting rise then fall of the engine.

With excruciating slowness the lights grew brighter through the rain. I began to make out the hotel and piers through the spray and mist. Still, I didn’t rush. No reason to push luck in the home stretch. We ran all the way up close to the beach, then swung hard to gain a following sea and pushed into the harbor. We preserved the silence as we found a moorage, tied up, and killed the engine. It was late, we were tired, and despite the cool rain I had sweat through my shirt. We walked up the ramp in search of dinner, begged some fish and chips from one of the only restaurants still open late into the evening but too busy to seat us. We waited outside on a bench for an hour while they snuck our order in. I watched the ocean crash violently, relentlessly, endlessly on the shore.

This story has been on my mind a lot as I work through the early phases of this new company. In many ways I feel like I’m back in that little boat, tossed to and fro by confused seas. Though the goal is on the horizon, tantalizingly close, progress means we aren’t always pointed straight at it. I know this is not the typical position a founder takes, as most prefer to say that everything is easy and perfect at all times, but I think it is the more realistic one.2 This is patient work, and there are many people in the proverbial boat with us — our families, our friends, our new team members, our investors, and our development partners. Some days it’s easy running, throttle wide open on sunny days sprinting at the target, laughing the whole way — and sometimes it’s the exact opposite. Yet those latter days are the most interesting, as we see what everyone — including ourselves — are made of.

But for me, at the wheel, even in the worst conditions I remember that not very long ago I stood on the shores of my sabbatical muttering, kicking rocks, commenting on the other boats coming or going, and watching weather blow through while wondering if I’d ever be out there again. So on the hard days I remind myself of a simple fact: I asked to be at sea. And I got it.

This last one, especially, should never be discounted. The only thing worse than turning the wrong way is not knowing what way to turn at all. Getting lost is the exponential mistake multiplier.

It always cracks me up that startups will be like, “we are tackling the most ambitious problem in human history!” And then the very next sentence say, “and we will have it solved in 6 months.” That should be the first litmus test for figuring out who’s full of it.