Carcinization 🦀

Escaping the evolutionary tendency to become a crab to pursue wonder for wonder's sake.

I joined the aerospace industry, fresh out of grad school, over a decade ago. I have written about the crazy interview that landed me there, which coincidentally was exactly twelve years as of last month. Even though that interview gave me a lot of hints at what was to come, I had no what I was actually getting into. The term “New Space” — that weird movement where VC-backed private companies claim they are commercializing space while actually pursuing huge government contracts — hadn’t even been coined yet.

Far from an industry leader, the company I worked for was regularly panned by industry experts, lobbied against, and outright maligned in the press; a complete 180 from where they are today. We were young, brash, and out to change the world.1 I spent the first year at that company thinking I wouldn’t last another day. Months passed like stressful years. After surviving the first year, I then spent the next nine convinced I’d never last a decade! Then one day I woke up, went to work, and released I’d passed that milestone, too.

And though many of the memories from back then only sweeten with time — adventures on launch sites with friends, the first time the company’s cargo capsule ever docked with the space station, watching rockets come down and blow up on a barge in the ocean — I realize how important it was that I get out of the New Space industry and started a long sabbatical last June.

In an industry where every year feels like ten, an actual decade is more than a career, or even a natural lifetime. Last year my heart joined my body in strongly signaling it was time to be done. Call it a felt century of chaos, adrenaline, pain, vigilance, and growth. The biggest thing I learned after my first hundred years? Only that I didn’t have another hundred in me.

I was burned out. And no matter what I tried to do to reset or recover, I felt a kind of shell hardening around me, a carcinization of self that I refused to let proceed. I needed a change, and left Launch Co., the company that I’d started and personally grown with, that had provided for my young family — and the families of my friends who worked there — through thick and thin. It was by no means an easy decision, but it was the necessary one.

The Journey Started with Wonder

A certain kind of magic surrounds the aerospace industry, and that magic is even stronger within the growing offshoot we call New Space. There are few places better suited to test one’s limits and there’s truly nowhere else you can have an outsized, sustained, and lasting impact while sending things (and sometimes humans!) to space. I often felt a deep wonder in some ancient part of me knowing that we can reach beyond the edge of our planet to sail the seas that would leave our ancestors speechless.

I felt connected to that wonder from a young age. When I was not yet even five, I treasured nestling in the safety of my Dad’s lap to watch PBS’ Nova as it rippled through space, shook down our roof mounted antenna, and came out our little TV. I’m too young to have seen Carl Sagan in his prime, but my Dad passed his same infectious spirit of wonder and exploration on to me. We’d lay at night on the frozen lake, down at the bottom of the hill below our house, letting the dust of galaxies gather in the corner of our eyes. I marvel, still, that a photon could travel millions of light years through space, wiggle down through our atmosphere, and somehow land right on my retina.

I believed that space exploration brought out the best in us, as a nation and as a species. It was just as much an ideal we worked to understand the shape of, as it was a place we actually sent humans and machines to grow our understanding of the universe. Only the best people worked on these systems, and only the best of the best rode them up past the sky. Of course, I had the movie Apollo 13 memorized.

As I grew older, my views sharpened a bit. I allowed that, sure, the early days of space were an overly romanticized veneer pulled over a brutal cold war and a weaponized race to the stars, but the wave of New Space that I’d been pulled into was different.

Right?

Everyone Becomes a Crab

Carcinization is a natural phenomenon by which any crustacean, given enough time, evolves into a crab. I learned this term when it popped up in the news cycle a few years ago, and I realized it perfectly described what was happening to me in the space industry. From the first moments of my first job a decade ago, I grew a hard shell to withstand the constant attacks that ostensibly centered on my work yet often turned bizarrely personal. I passed a few years, safe in my shell, continuing my journey peacefully.

Over time, my responsibilities grew, and I found that it was easier to play offense than defense. No one attacks someone they think might hit back. In that spirit, I grew pinchers and learned how to use them. I also developed a strong radar for the type of people around me. To this day, I can still see an insecure tech boy coming from a mile away. To mask his own insecurity, he’s going to be the loudest, brashest, most confrontational asshole in the meeting. I used my pinchers, innocently at first, to drive those people away. Later, I began to use them to mask my own insecurities in my work and self.

As more responsibilities landed on my plate — running systems, to running teams, to running entire projects like the landing barge — I had less and less emotional reserves left to deal with the human element of my role. Further, as the pace ramped up, I didn’t have time to properly guide people or care for myself. There was never enough time to properly explain things, to onboard people into new roles, to even stop and have a complete thought. I ate my meals on the go, doled out my orders on the go, and meted out my version of perceived justice on the go. Where once there was space for thoughtful conversations and advice, there remained only room for curses and rushed impatience with everyone and everything around me that wouldn’t match the speed with which I conducted my life.

Adopting this attitude was the final step in becoming a crab.

Trying a Different Path

Look, I hope it goes without saying that I don’t want to be a crab. It’s exhausting and, though I was unfortunately damn good at it, it’s not my natural or best state of being. As much as I wanted out, I didn’t know how and I didn’t think I was worth making the change for. But I watched as my friends, one by one, changed too. Giving in to the evolutionary pressures, they began to strafe and pinch, and to subsist greedily on whichever of our peers’ careers washed up on the proverbial tideline. This was enough to force a change.

I left the company entirely and set off on my own2. The first business I tried failed, and I found myself as a single dad in dire need of diaper money. So, I went back to the New Space industry. I didn’t have much choice, it seemed. However, instead of joining a space company I started my own, one that would solve problems for the majors. I figured that degree of separation might be enough to keep the crab at bay. I vowed that “this time would be different!” and, though it was, new pressures restarted my personal carcinization in ways I never saw coming.

For a while, my team and I became lost in the doing, joyously discovering we could support ourselves on our terms doing work we cared about and understood. I marveled as we quickly went from one person, to two, all the way up to our high point of 30 team members as we solved problems for space companies across the United States. We designed and built hardware from our home in Alaska, showing our neighbors that new industries are possible here. Our core driving principle, our oft-repeated mantra, was “there’s no point in going to space if we’re all miserable when we get there.” We fired clients that were impossible to work with, and worked hard to push back on ridiculous requests. We took Fridays off in the summer, and mostly worked 40-hour weeks. I thought I had it solved.

Though we fostered joy inside our company and in relationship with one another, my work as the primary interface to the wider industry exposed me to new pressures that mounted and inexorably restarted my crabby metamorphosis.

Pressure from clients that wanted us to perform miracles for low wages and, by God, right this minute. Clients that tried to talk us into cutting corners on the design process due to their tight budget or artificially compressed schedule, only to lambaste us eight months later for letting them take such a shoddy approach.3

Pressure from running a bootstrapped company in an industry that was artificially propped up by free-flowing venture capital in the single longest bull market in the history of the stock market and watching as it began to teeter. Every slide in every pitch deck that talked about future customers looking like a multitudinous “Spiderman-pointing-at-Spiderman” meme of every venture-backed company incestuously indicating one another as their core future clientele.

Pressure from watching the trickle-down of benefits to friends and colleagues slow, then stop, as once hot companies folded, and the value of their stock options dove toward zero. Some friends close to retirement left with nothing, while their executives drifted back down to earth on golden parachutes. The way my friends inevitably discovered the limits of the supposed human-centered vision of their company; where the slogans about working for all humanity stopped and the need to exploit the well-being of actual humans began.

Pressure from navigating the tiny, closed ecosystem of New Space, and realizing that even for my small company, the only source of sustenance, the only real, long-term, viable customer in the industry, is a government department that innocently claims defense while seemingly fixating on just the opposite.

Pursuing Wonder

Alright, deep breath, woosah, et cetera.

I promise I don’t have an axe to grind.4 If I get too fired up or come off as too critical, just know that it’s because I care too deeply. I am not a cynic. I truly love building things. I love the process, the alchemy, and the satisfaction that comes from building things — and most especially from building them well.

The long story above is meant to set the stage, and to provide a shared context before bringing things back to the realm of the constructive. In short, I think there is a path before us — but it is a narrow one and I am still struggling to discover it myself. If we continue to use space and the space industry as our example, we can pose the dilemma as the difference between what I’ll call the “Sagan view”5 of exploration, and the “billionaire view.” And we can tap into the dichotomy with one simple question:

When was the last time we pursued wonder for wonder’s sake?

Don’t scoff at the question and move on. Stop, and sit with it. When was that, really? When was something so worth doing that you did it to the best of your ability with no regard for what it might do for you?

Look at the images in the gallery below. What do they inspire in you? Even in this new age of CGI, AI, and deep fakes, these photos from deep space inspire absolute wonder in me. I can’t believe that in my lifetime I am able to see high-resolution images of the aurora on Jupiter, gravitational lensing of countless distant galaxies spun out on infinite axes, methane ice caps on Pluto, and more dramatic pictures of Saturn’s rings than I can fit in a single Substack gallery.

We respond to images like this with our hearts. I would wager that the majority of people who end up in the space industry end up there because of their hearts, rather than their minds. Don’t get me wrong — a strong and trained mind is required! But it can’t be the only thing, and increasingly I don’t think it should even be the leading thing.

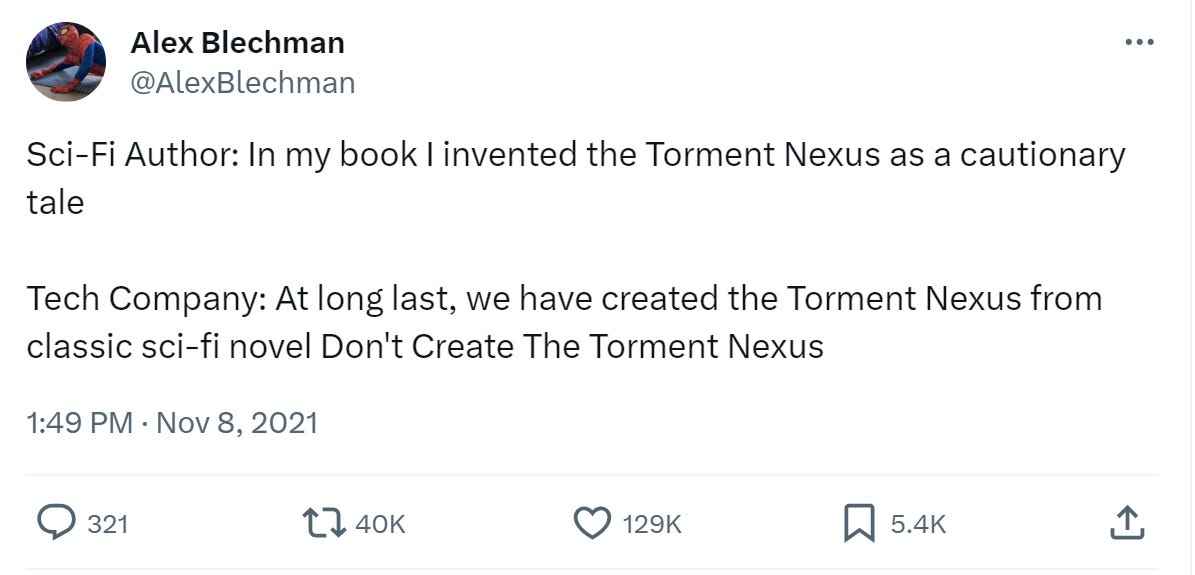

It’s strange to see the future we were warned about in sci-fi from people like Asimov become heralded as the next great advancement for society. As Ted Gioia eloquently wrote in The Honest Broker last month, progress is not progress unless it helps humans to flourish. Everything these days seems to be designed for just the opposite. It’s even become a meme (see below). Which of the next slew of “advances” now tottering over the distant horizon truly excite? And do they remain exciting when we realize how they’ll make money, and who they’ll make it for?

Like I’ve written before, everything is a scam.6 I am not naive enough to think that’s unique to our present time, but the sheer scale that scams can be perpetuated on likely is. We are awash in utter bullshit designed to separate us from our dollars either in a single bulk transaction or slowly over many years by exacting endless $5 per month service tolls7.

In my world of building big, complex hardware scams show up as flashy pitches, big rounds of cash, and then perpetual crickets.8 I worry what this does to us as a species. What happens when this current hardware-rich blip produces nothing? When, inevitably, the hype meets reality and vaporizes in a flash? Where do we go from there? What do we place our hopes in? There isn’t another convenient vessel to transplant humanity’s hope into. If, and when, this current New Space fever breaks, I fear we’ll be left with little. That may (rightly) cause people to throw up their hands, and perhaps even argue that we cannot build anything anymore, and therefore that we should not even bother dreaming.

The Narrow Path

And yet, despite these scams, and my own lived experience on the front edge of New Space, I, too, dream of humanity moving out among the stars, setting foot on the moon or the Red Planet and building some kind of presence there. Exploration lives in our DNA, and I am no exception. I feel the pull of the new and the unknown, that same wondering force that sent me out over frozen inlets on dark winter mornings in my childhood and keeps pushing me to find the edges in everything I’ve done since.

It’s precisely because I am no exception that I feel so burned by the priorities of the tech industry. It’s precisely because I subscribed to the mythos of the solitary inventor, the chosen one who could solve humanity’s struggles, that I now strongly warn others against it.

I don’t think we need to give up exploration or progress. There’s a middle path: Choose the path of serving humanity in whatever way you can and walk it with wonder. That means instead of focusing on doing the flashiest thing possible, find something you’re good at, let go of any preconceived ends, and instead surrender entirely to the means.9

We each know those places we get lost in the doing. You know your places. Mine are playing music, writing, and building things. From those simple things, more complex things arise, much the same as simple machines work together to make more complex ones. Flying as a private pilot is one such thing for me, a complex task built from a love of rhythm, order, and working with my hands. If you don’t know what those things are for you, maybe you’ve just forgotten. That’s ok, I forgot for a long time, too.

Doing this work, and the imperfect attempt to walk this path, has helped me shed the pinchers and shells and crabby attitude that once defined my existence. I have been able to break free of the carcinization that once threatened to swallow me whole. Now the work of showing others, and building new things the right way, begins.

Yes, I know that wanting to ‘change the world’ is a dangerous delusion, that’s the point. More here.

I had tried this before and failed.

Our friendly approach was famous. Multiple clients mused over the years that they couldn’t believe we were so nice to them! Yet, somehow, those same clients couldn’t find it in themselves to act the same way.

I ground my axe for years. Like pissing and moaning on Twitter, it’s not truly satisfying. I want to be constructive.

I realize this might mean different things to different people. I pitched this to Pete Worden over a dinner. He rolled his eyes and told me he preferred the “Arthur C. Clarke” vision. I’ve heard Asimov come up too. These are both fine substitutes.

Since I limit myself to one (1) rant per post, I am simply linking to my other one. Loophole!

Honestly, I pine for the halcyon days of my youth when the monthly music and movie streaming subs were closer to $5. Is this the right time to announce I’m making this a paid substack? jk.

Watch the hyperloop (which was only conceived of to distract from high-speed rail) evolve from vacuum-tube maglev train to Teslas in a tunnel, for one of dozens of examples.

Put another way, it’s “leaving the fruits of dharma.” We must do the best work we can, yet leave the results of that work.

That was an interesting insight into something I know very little about. I don't know much about old space space. I really liked this phrase "a felt century of chaos" - what a zinger, a felt century of chaos. A delightful combination of words, and no mistake